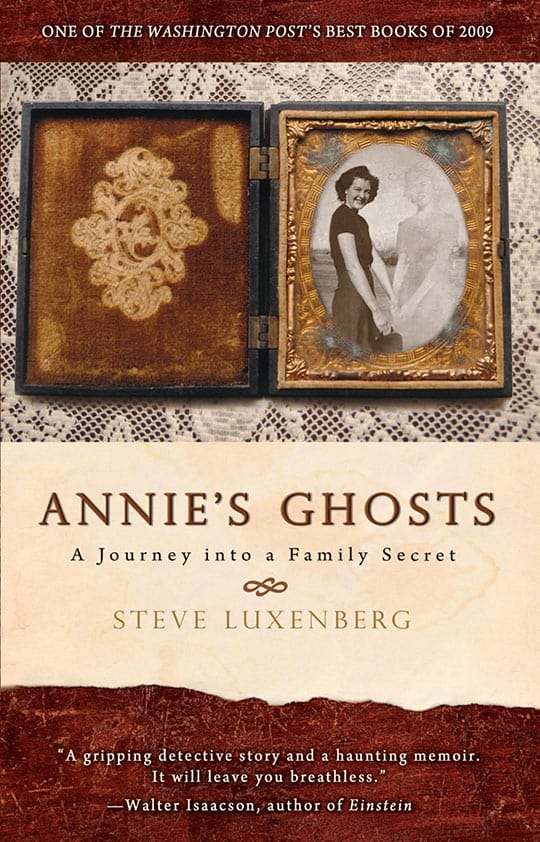

Annie’s Ghosts

A Journey Into a Family Secret

The Great Michigan Read, 2013-14

Michigan Notable Book, 2010

Washington Post, Best Books list for 2009, memoir

Beth Luxenberg was an only child. Or so everyone thought. Six months after Beth’s death, her secret emerged. It had a name: Annie.

Steve Luxenberg’s mother always told people she was an only child. It was a fact that he’d grown up with, along with the information that some of his relatives were Holocaust survivors. However, when his mother was dying, she casually mentioned that she had had a sister she’d barely known, who early in life had been put into a mental institution. Luxenberg began his research after his mother’s death, discovering the startling fact that his mother had grown up in the same house with this sister, Annie, until her parents sent Annie away to the local psychiatric hospital at the age of 23.

Annie would spend the rest of her life shut away in a mental institution, while the family erased any hints that she had ever existed. Through interviews and investigative journalism, Luxenberg teases out her story from the web of shame and half-truths that had hidden it. He also explores the social history of institutions such as Eloise in Detroit, where Annie lived, and the fact that in this era (the 40s and 50s), locking up a troubled relative who suffered from depression or other treatable problems was much more common than anyone realizes today.

Praise

“Steve Luxenberg’s hunt for the story of his hidden aunt is both a gripping detective story and a haunting memoir. It will leave you breathless. The personal tale is astonishing, and Luxenberg uses it to explore, in a deft and poignant way, the nature of secrets, memories, historical truth, and family love.” ―Walter Isaacson, bestselling biographer (Leonardo da Vinci, Einstein, Steve Jobs)

“Annie’s Ghosts is perhaps the most honest, and one of the most remarkable books I have ever read. . . From mental institutions to the Holocaust, from mothers and fathers to children and childhood, with its mysteries, sadness and joy—this book is one emotional ride.” ―Bob Woodward, author of Fear: Trump in the White House and other bestsellers

“Invoking the precision and restraint of first-rate journalism, Steve Luxenberg peels back the skin of his own family and discovers much to love, much to consider and more than enough to shatter hearts. Unlike many who claim the mantle of the investigative reporter, this is the work of someone who understands that truth is fragile, complicated and elusive.” —David Simon, creator of HBO’s The Wire

“Steve Luxenberg sleuths his family’s hidden history with the skills of an investigative reporter, the instincts of a mystery writer, and the sympathy of a loving son. His rediscovery of one lost woman illuminates the shocking fate of thousands of Americans who disappeared just a generation ago.” ―Tony Horwitz, author of Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War

“Steve Luxenberg, a gifted storyteller in possession of the full arsenal of journalistic tools, trains his sights on a private mystery: Why did his mother carry to the grave the secret that she had a sister? His discoveries reveal the hidden-in-plain-sight mid-century world of the terrible decisions facing a family crippled by an imperfect child… Luxenberg’s beautiful book is in part the story of secrecy itself, when words carried mysterious power and wounds could not be healed through forgiveness.” —Melissa Faye Greene, author of The Temple Bombing and Last Man Out: The Story of the Springhill Mine Disaster

Reviews

“As Luxenberg slowly uncovers Annie’s story, he realizes that by exposing one ghost, he exposes thousands. . . The author calls on his investigative reporting skills not just to uncover the facts, but to explore what happens when lies or omissions become truth, exposing the contradictions, contrasts and parallels that exist within every life, every relationship and every family. Beautifully complex, raw and revealing.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“Beth told her son often that she loved him. Annie’s Ghosts is his elegy in return, a poignant investigative exercise, full of empathy and sorrowful truth.” —Barry Werth, The Washington Post

“Most books can be described in a word—mystery, biography, memoir, history, travelogue. Steve Luxenberg’s “Annie’s Ghosts” is all of these and more. . . . For me, the word to describe this book: Unforgettable.” ―Javan Kienzle, Detroit Free Press

“The book’s first lines hint at the magic that Luxenberg will weave with his tale, a story as compelling as anything found in fiction. . . Annie’s Ghosts is a meticulous reporter’s journey to put all the pieces in their proper place. But it is with a storyteller’s panache that he leaves us breathless while he spins his tale.” —Sienna Powers, January Magazine

“… a fascinating family memoir and thrilling detective story…” — The Buffalo News

“Part memoir, part mystery, part history of the mental health movement, Annie’s Ghosts is a fascinating account of a life lived in the shadows and a family beset by despair.” —Allison Block, Booklist (starred review)

“Annie’s Ghosts is an exhaustively researched, often moving testament to the ties that bind families together—including connections we aren’t even aware existed.” —Mary Carole McCauley, The Baltimore Sun

“Luxenberg dons many hats in this masterful piece of work; he is simultaneously a historian on Jewish immigration, a Holocaust researcher, an investigative reporter, a memoirist and always a grieving son.” —Elaine Margolin, The Jerusalem Post

“Luxenberg pulls what he knows of his family’s secret out of the closet and examines it in exacting detail . . . Those facts tell their own haunting story, not about ‘ghosts’ but of a girl named Annie, who was absent from her own life.” —Diane Scharper, The Weekly Standard

“Readable and compelling, emotional and just plain interesting, Annie’s Ghosts is a tragic family saga that pushes the narrator to examine his role as a son versus that of a writer and asks readers to find some sympathy and understanding for a family damaged by secrets and lies, and yet still bound by love and hope.” —Sarah Rachel Egleman, bookreporter.com

Prologue

Spring 1995

The secret emerged, without warning or provocation, on an ordinary April afternoon in 1995. Secrets, I’ve discovered, have a way of working themselves free of their keepers.

I don’t remember what I was doing when I first heard about it. If I had been thinking as a journalist rather than as a son, I might have made a few notes. As it is, I’m stuck with half-memories and what I later told my wife, my friends, my newsroom colleagues—and what they recall about what I told them.

Just as secrets have a way of breaking loose, memories often have a way of breaking down. They elude us, or aren’t quite sharp enough, or fool us into remembering things that didn’t quite happen that way. Yet much as a family inhabits a house, memories inhabit our stories, make them breathe, give them life. So we learn to live with the reality that what we remember is an imperfect version of what we know to be true.

What I know for certain is this: On that spring afternoon in 1995, I picked up the phone and heard my sister Sashie say something like, “You’re never going to believe this. Did you know that Mom had a sister?”

Of course I didn’t know. My mother was an only child. Even now, I can hear her soft voice saying just those words. “I’m an only child.” She told that to nearly everyone she met, sometimes within minutes of introduction. She treated her singular birth status as a kind of special birthright, as if she belonged to an exclusive society whose members possessed an esoteric knowledge beyond the comprehension of outsiders.

She suggested as much to my wife Mary Jo during their first getting-to-know-you conversation. That was 1976, four years before Mary Jo and I were married. The two of them, girlfriend and mother, were sharing a motel room while I recuperated from an emergency appendectomy that had abruptly ended a weekend camping trip. (I still wince at the memory, and I’m not referring just to the surgery.) As soon as Mom learned of my plight, she hustled to the Detroit airport and found her way to rural West Virginia. During their evenings together in the motel, Mom made a big point about how she felt an unusual connection to Mary Jo, her fellow traveler in the only-children club. “I understand what it’s like,” Mom assured her. “I know how it is to grow up without brothers and sisters.”

It never occurred to me that it was a little odd how often Mom worked those “only child” references into her conversations. I simply accepted it as fact, a part of her autobiography, just as I knew that her name was Beth, that she was born in Detroit in 1917, that she had no middle name, that she hated her job selling shoes after graduating from high school, that she would have married a guy named Joe if only he had been Jewish, that she was the envy of her friends because of her wildly romantic love affair with my Clark Gable look-alike father, that she was kind and generous and told us growing up to, above all else, always tell the truth.

A sister?

“Where did you hear that?” I asked Sashie.

Sash and I are close, although she is 12 years older. When I first learned to talk, I couldn’t say her name, Marsha. What came off my untrained tongue sounded something like “Sashie.” The mangled pronunciation stuck. She is Sashie, or Sash, even to her husband and some of her friends.

As Sash would say, Mom was not in a good place in the spring of 1995. Her health, and her state of mind, were often topic A in the long-distance phone calls among her children. (Our family, like many, is a complicated one. My parents, Beth and Jack, married in 1942 and had three sons. I’m the middle one; Mike is seven years older, and Jeff is three years younger. Sash and her older sister, Evie, were my father’s children from a first marriage that lasted seven years. The girls lived with my parents for a large chunk of their childhood, particularly Sash, who thinks of herself as having grown up with two families and two mothers—and double the worry when both Moms began having health problems as they aged. Evie moved out just before I was born, so I never knew her nearly as well as I knew Sash, my “big sister;” Sash married and left the house when I was about eight, but our relationship remained close as we managed that tricky conversion from childhood to adulthood.)

My mom was still working at 78 years old, still getting herself up every morning and tooling down one of Detroit’s many expressways to her bookkeeping job at a tiny company that sold gravestones, a job she had been doing for more than 30 years. But her emphysema, the payoff from a two-pack-a-day smoking habit that began in her teens, had gotten worse. So had her hearing; she fiddled constantly with her hearing aid, frustrated that she could no longer understand the quick mumbles that punctuate everyday conversation, but also frantic to avoid the sharp whines that burst forth from the tiny device whenever it picked up a sudden loud noise, such as the shrieks of happy grandchildren.

On top of Mom’s periodic trips to the ER for shortness of breath, her doctors believed that she was suffering from anxiety attacks. It was a chicken-and-egg problem: The shortness of breath made her anxious, and her anxiety triggered the feeling that she couldn’t breathe. She emerged from a February hospitalization with a fistful of prescriptions and a fear that her days of good health were behind her. The Xanax made her less anxious at first, but within a few weeks, she was fingering the medication as the cause of her insomnia and jitters. “It makes me want to crawl out of my skin,” she said.

As if that wasn’t enough of a roller coaster ride, she was following doctors’ orders to quit smoking. She called cigarettes her “best friends” in times of stress, and these were certainly stressful times, for her and for us. There was so much going on with her—the nicotine withdrawal, the reaction to Xanax, the shortness of breath, the sleepless nights—that it seemed impossible to find a way back to the equilibrium that had once ruled our lives. We bounced back and forth, thinking one minute that everything would work out if she would just give the medication a chance, and the next, thinking that, no, this was crazy, the medication was the problem, maybe everything depended on getting her doctors to switch her to some other magic pill.

She had been feeling so lousy that she didn’t even want to drive. That was a bad sign. Henry Ford himself would have smiled to hear her talk about driving with my father during their courtship days, the feeling of flying along on the open road, your hair free in the wind, the sense that the world was yours for the taking as long as you had wheels. Not even Dad’s sudden death in 1980, which sent Mom reeling like nothing else I had ever seen, had slowed her down. Her Chevrolet Beretta wasn’t just a car; it symbolized her independence, her vitality, her youth and her freedom.

But for several months now, Mom had left her car at home, relying instead on a counselor at Jewish Family Service, social worker Rozanne Sedler, to take her to various doctors’ appointments. Rozanne had gotten to know Mom pretty well during their car rides and counseling sessions, and had urged her to visit a psychiatrist. Mom, who had always disdained psychiatrists and psychiatry, consented to go—another sign that she was not in a good place.

When I heard Sash’s voice on the phone, I assumed Mom had landed back in the hospital. But a sister?

Looking back, it’s startling to me that I can sum up all we learned initially about Mom’s secret in just a few sentences. Mom had mentioned, at a medical visit, that she had a disabled sister. She said she didn’t know what had happened to this younger sibling—the girl had gone away to an institution when she was just two years old and Mom was four. Rozanne was confused when she heard this; Mom had already informed her, during their many times together, that she was an only child. So Rozanne called Sash to resolve the contradiction.

That was it. So little information, so many questions. Institutionalized? For what? Was Mom’s sister severely disabled? Mentally ill? A quick calculation: If Mom was four, then her sister went away in 1921. What sort of institutions existed in Michigan during that time? I had no clue. Was it possible that her sister—my aunt—was still alive? What was her name? Could we find her? Would Mom want us to find her?

Sash and I had long conversations about what to do. The dominant word in our discussions, as I remember them now, was “maybe.” Maybe it wasn’t so odd that Mom hadn’t mentioned it. Maybe Mom called herself an only child because she never knew her sister. Maybe it wasn’t our place to ask her about it. Maybe we should let her tell us.

So we decided not to press Mom about it. After all, we reasoned, Mom had chosen to hide her sister’s existence all these years. She hadn’t told any of us before, and even now, she hadn’t told us directly. We weren’t even sure that Mom knew that we knew. In fact, we were pretty sure that she didn’t. Rozanne had only brought it up because she was perplexed by the discrepancy. She couldn’t know that her simple query would land like a bombshell.

Besides, this wasn’t the best time to probe Mom’s psyche. Her anxiety level had reached a point of incapacitation. Mom’s psychiatrist, Toby Hazan, had concluded that depression, not anxiety, was at the root of her problems. He wanted to take her off Xanax and treat her with an antidepressant that, in rare cases, could lead to respiratory arrest. Mom’s emphysema increased the risk. Hazan didn’t feel comfortable putting her on the medication at home; he recommended that Mom voluntarily enter a psych ward for a two-week treatment regimen, which would allow him to monitor her closely for any adverse side effects.

Naturally, Mom resisted. Whenever I called her, as my siblings and I were doing almost daily, concern about her health trumped any curiosity about an unknown sister. It didn’t seem fair to ask her now, when she was so vulnerable. Best to wait, I thought, for her return to the strong, self-sufficient woman we had always known.

Besides, she was as much in the dark about her sister as we were. It seemed pointless to ask her a lot of questions. She might feel betrayed if we revealed that we knew, and to what end?

THAT QUESTION HUNG in the air when Sash went to visit Mom several weeks later. Her report wasn’t good. “I just spent the worst night of my life,” Sash told me during an early morning phone call. Mom had sat on the side of her bed most of the night, moaning and groaning, Sash said, and yet didn’t seem physically sick. She wasn’t eating well, and she was too jittery to keep up with the cleaning, so the apartment wasn’t in its usual spit-spot condition.

“You want me to come out there, don’t you?” I said.

“Yes.”

Sash has no trouble being straightforward; that’s been her modus operandi most of her life. I learned long ago to deal with her no-nonsense style, and even to appreciate it. If nothing else, it simplifies decision-making that otherwise might drag on, to no one’s gain. By early evening, I was sitting in Mom’s apartment.

That night was a rerun of the previous one. Moans, groans, no sleeping for Mom, or for us. The following afternoon, in a hastily arranged meeting in Dr. Hazan’s office, Mom reluctantly agreed to sign herself into the geriatric psych ward at Botsford Hospital so she could get off the Xanax and start taking the antidepressant.

It seemed the best of the options, and we needed to do something. We took Mom there the next day around 5 p.m., as soon as a bed became available, and left her there for the night. At 7:30 a.m., the phone rang. “Steven,” she said, panic evident in her voice, “you have to come take me home. I can’t stay here, Steven. You don’t understand. This is not the right place for me. I made a mistake coming here.”

I stalled for time to think, unwilling to say anything I might regret. Inside, though, I had plenty of sympathy for her reaction. I had seen the other patients on the ward; everyone was suffering from Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia. Grim was not too strong a word for what she was facing.

“Mom, we’ll be there soon,” I said. “We can talk about it then.”

“You don’t understand,” she said. “They took away my pencils. I can’t even do a crossword puzzle.” That was bad. Finishing the daily crossword, she often said, was her way of proving to herself that she still had all her marbles.

“We’ll be there soon, Mom.”

If that earlier night had been the worst of Sash’s life, then that Friday was the worst day of mine. On the way to the hospital, Sash warned me that Mom would put on a full-court press, begging to go home. Sash had already concluded that Mom needed to stay, but I was ambivalent. “If you decide to take her home,” Sash said, with her usual directness, “I can’t be a party to it.” So the pressure was on me.

Mom wasted no time making her case. She was unrelenting. I can still remember sitting tensely in a chair, in the ward’s bright and airy day room, with Mom draping herself over my back, cajoling, coaxing, crying, sweet-talking. “I can’t stay here,” she pleaded. “Steven, please, please. I’ll do anything you say, if you just take me home.” Our roles had reversed: She was the child, employing every manipulative trick to get her way. I was the adult, resisting, observing, comforting her as I tried to figure out the right thing—or at least the best thing—to do.

It took all my strength not to give in. I tried not to cry, and I failed. If seismographs could measure tremors in the human voice, I’m sure that mine registered a slight earthquake on the Richter scale. As gently as I could manage, I told her that we couldn’t just go home, that she wasn’t really able to take care of herself, that the hospital was the best alternative. I had no idea what else to say, and no idea that her obvious terror came from some place other than watching the demented patients around her. “I can’t stay here,” she repeated, like a mantra. “Please don’t leave me here alone.”

“It’s two weeks, Mom, that’s all,” I said. “You’ll be home in two weeks. We’ll talk to you every day. You won’t be alone.”

I took a good, long look around, and what I saw depressed me, too: patients who couldn’t feed themselves, patients muttering unintelligibly, patients exhibiting every form of senility I could imagine. Mom was the healthiest person there, by far, and it made me cringe to think that I would be leaving and that she would be staying. That vision of Mom, surrounded by dementia patients, trying to get a pencil so she could do her damn crossword puzzle, stayed in my head. I retreated to a nearby room to make some phone calls to other facilities, hoping to find something better. I found one with a much younger clientele, primarily teenagers who had tried or were threatening to kill themselves. What a choice: Suicide or senility. Take your pick.

As soon as I returned to the day room, Mom resumed her campaign. “Please, Steven, please. I can’t stay here.” It went on for what seemed like hours. Late in the afternoon, the three of us—Sash, Mom and I—met with Hazan in one last attempt to settle her down. Hazan’s notes on the meeting are part of Mom’s hospital record.

If you leave the hospital, Hazan asked her, what will you do?

“I have no plan, I just want to go out,” Mom said angrily. “I don’t think this is the right place for me. This is not home.”

Home, Hazan bluntly reminded her, had become hell—sleepless nights, moaning, groaning.

“My mind tells me I should stay here,” Mom conceded. “Rationally, I know I should stay here.” Then, desperately, she turned to me. “Please, I just can’t take it.”

Sash couldn’t take it either. She left the room. I looked at Mom. The sight was not pleasant. Her glasses magnified the tears in her round, expressive eyes. Her face, so striking when she smiled, sagged under the pressure of the long day and the exhaustion of several sleepless nights. Her blouse hung loosely on her bony shoulders. She had lost 25 pounds from her 5 foot, 6 inch frame over the past two years, so she now weighed less than 100. My heart went out to her, but my head told me that it would be a mistake to take her home.

“Mom, I think you should stay for a few days. As Dr. Hazan said, the law allows him to keep you for three. If you want to leave after that, even though he’s saying that it’s against his best judgment, you can sign yourself out.”

I had abandoned her cause. Her son, her own flesh and blood, had gone over to the other side. Out of options, she gave up the battle, at least for that moment. The look of pure fear remained in her eyes, though—a fear that I wouldn’t truly understand until much later, when I learn the truth about Mom’s sister—and that’s the image that stayed with me long after Sash and I exited the hospital and drove away in May’s cool night air.

TWO WEEKS LATER, her new medication working well, Mom went home. My older brother Mike flew in from Seattle to help her for a few days. A month later, she told Hazan she felt “fantastic.” She had survived the ordeal; so had we.

While she was sick, it never seemed like the right time to ask her about her sister. Now that she was doing better, Sash and I thought she might reveal the secret on her own. But she never did. So we let it rest. Hard as it is for me to fathom this now, we never asked her about it; since she didn’t know anything about her sister’s fate, I guess I didn’t see much point.

Mom went back to work, back to driving herself, back to the independent life that had once seemed gone forever. We cheered, even as we kept trying to persuade her that she might be better off moving closer to one of us. Then, catastrophe: On the afternoon before her grandson’s wedding in September 1998, while smoking a cigarette outside the entrance to a non-smoking Seattle hotel, she was knocked off her feet by the automatic sliding door, breaking her pelvis and sending her into months of painful rehabilitation. Exhausted, she never quite recovered.

She died in August 1999, her secret intact, as far as she knew—until six months later, when it surfaced once more, unforeseen, uninvited, nearly forgotten.

This time, though, the secret had a name.

© Steve Luxenberg, 2009

Cast of Characters

Primary figures

Beth (maiden name Cohen) Luxenberg, daughter of Hyman and Tillie Cohen (born 1917 in Detroit, died 1999)

Annie Cohen, hidden younger sister of Beth (born 1919 in Detroit, died 1972)

Steve Luxenberg, son of Beth and Jack Luxenberg; narrator of Annie’s Ghosts (born 1952)

Relatives

The Schlein and Cohen families (Detroit and Radziwillow, Russia/Ukraine)

Hyman Cohen (Chaim Korn), Beth and Annie’s father, junk peddler and immigrant from Radziwillow (arrived 1907, died 1964)

Tillie (Schlein) Cohen, Beth and Annie’s mother, immigrant from Radziwillow (arrived about 1914, died 1966)

Anna (Schlajn/Schlein) Oliwek, Beth’s cousin; a Holocaust survivor from Radziwillow who met the Cohen family after 1949, the year of Anna’s arrival in the United States (born 1923, deceased)

Nathan Shlien, Anna’s uncle and a boarder with the Cohens in 1930, before Annie became a secret (born 1894, deceased)

Bella and David Oliwek, Anna’s daughter and son, who as children accompanied their mother on a few trips to Eloise; Dori Oliwek, their younger sister

The Luxenberg family (Detroit, Syracuse, N.Y., and Lomza province, Russia/Poland)

Julius Luxenberg, known as Jack, Beth’s husband, son of Harry and Ida Luxenberg, (born in Lomza 1913, arrived in the United States 1920, died 1980)

Harry Luxenberg, Jack’s father, a baker and immigrant from Lomza (arrived 1913, deceased)

Ida Luxenberg, Jack’s mother, immigrant from Lomza (arrived 1920, deceased)

Manny Luxenberg, Jack’s younger brother (born 1921, deceased)

Rose (Luxenberg) Boskin, Jack’s sister (born 1925, deceased)

Bill Luxenberg, Jack’s youngest brother (born 1929, deceased)

Evie (Luxenberg) Miller, Steve’s eldest sister; Jack’s daughter from a first marriage (born 1937)

Marsha (Luxenberg) Rosenberg, known as Sash or Sashie, Steve’s older sister and Jack’s daughter from a first marriage (born 1940)

Michael Luxenberg, son of Beth and Jack, Steve’s older brother (born 1945)

Jeffery Luxenberg, son of Beth and Jack, Steve’s younger brother (born 1956)

Other Significant or Recurring Figures

At Botsford Hospital (general hospital in Farmington, Mich., where Beth was treated)

Time Frame: 1995-1999

Toby Hazan, Beth’s psychiatrist

Mary Bernek, psychiatric social worker

Rozanne Sedler, social worker for Jewish Family Service (not associated with Botsford)

At Harper Hospital (general hospital where Annie went for medical care)

Time Frame: 1937-1940

Frederick Kidner, noted orthopedic surgeon who decided to amputate Annie’s leg

Stephen Bohn, neurologist who suggested that Annie’s family institutionalize her

Jean Powell, social worker who first dealt with the Cohen family in the mid-1930s

At Wayne County Probate Court

Time Frame: 1940

Patrick O’Brien, Wayne County Probate Court judge who approved Annie’s commitment to Eloise in April 1940

Benjamin W. Clark, Howard Peirce and Peter E. Bolewicki, physicians assigned by O’Brien to examine Annie and offer an opinion on her sanity

At Eloise Hospital (county institution where Annie lived, Wayne County, Michigan)

Time Frame: 1940-present

Mona Evans, social worker and author of a lengthy report on Annie (“Routine History”) after her admission to Eloise in 1940

Thomas K. Gruber, superintendent, 1929-1948

Edward Missavage, staff psychiatrist for nearly 30 years and former director, male psychiatric division

Jo Johnson, coordinator, Friends of Eloise; chairman, Westland Historical Commission

Martine MacDonald, artist and co-originator of “Resurrected Voices: The Eloise Cemetery Project”

Beth’s Friends and Neighbors

Time frame: 1930s-1942

Faye (Levin) Emmer, a close friend who appears in many of Beth’s photos from the 1940s (deceased)

Sylvia (Robinson) Pierce and Irene (Robinson) Doren, sisters who lived next door to the Cohen family on Euclid Street (both deceased)

Millie (Moss) Brodie, a cousin of Sylvia and Irene, visitor to Beth’s neighborhood

Martin Moss, known as Marty; Millie’s brother and Beth’s friend

Julie Reisner (Norton), friend of Beth, Sylvia, Irene and Faye

Time frame: 1942-1950

Fran (Rumpa) Donofsky, Beth’s close friend during World War II who later married Jack Luxenberg’s cousin, Hy Donofsky

Medji Grobeson, sister of Jack’s first wife, Esther; babysitter used by Beth in the mid- to late 1940s (deceased)

Time frame: 1950-1999

Ethel Edelman, member of Beth’s bridge group and Beth’s closest friend from her days on Houghton and Fargo in Detroit (deceased)

Ann Black, bridge game partner

Marilyn Frumkin, bridge game partner and wife of Sid Frumkin, Beth’s long-time boss (both deceased)

Fred Garfinkel, Beth’s co-worker and boss

Natalie Edelman, Ethel’s daughter

Reflections on Writing Annie’s Ghosts

When I heard that my mother had been hiding the existence of a sister, I was bewildered. A sister? I was certain that she had no siblings, just as I knew that her name was Beth, that she had no middle name, and that she had raised her children to, above all, tell the truth.

Part memoir, part detective story, part history, Annie’s Ghosts revolves around three main characters (my mom, her sister and me as narrator/detective/son), several important secondary ones (my grandparents, my father and several relatives whom I found in the course of reporting on the book), as well as Eloise, the vast county mental hospital where my secret aunt was confined—despite her initial protestations—all of her adult life.

As I try to understand my mom’s reasons for hiding her sister’s existence, readers have a front-row seat to the reality of growing up poor in America during the 1920s and 1930s, at a time when the nation’s “asylums” had a population of 400,000 and growing. They will travel the many corridors and buildings of Eloise Hospital, a place little known outside Detroit but which housed so many mentally ill and homeless people during the Depression that it become one of the largest institutions of its kind in the nation, with 10,000 residents, 75 buildings, its own police and fire forces, even its own dairy.

Through personal letters and photographs, official records and archival documents, as well as dozens of interviews, readers will revisit my mother’s world in the 1930s and 1940s in search of how and why the secret was born. The easy answer—shame and stigma—is the one that I often heard as I pursued the story. But when it comes to secrets, there are no easy answers, and shame is only where the story begins, not ends.

Whenever the secret threatened to make its way to the surface, Mom did whatever she could to push it back underground. Just as Annie was a prisoner of her condition and of the hospital that became her home, my mother became a virtual prisoner of the secret she chose to keep. Why? Why did she want the secret to remain so deeply buried?

Employing my skills as a journalist while struggling to maintain my empathy as a son, I piece together the story of my mother’s motivations, my aunt’s unknown life, and the times in which they lived. My search takes me to imperial Russia and Depression-era Detroit, through the Holocaust in Ukraine and the Philippine war zone, and back to the hospitals where Annie and many others languished in anonymity.

Q&A

Steve invited Laura Wexler, author of Fire in a Canebrake: The Last Mass Lynching in America to conduct a Q&A. Wexler is a writer and editor who lives in Baltimore, and a faculty member in Goucher College’s Master of Fine Arts program in nonfiction writing. The interview was conducted in 2009.

Q. You say several times in Annie’s Ghosts that you were working to balance your role as a reporter and as a son. Can you discuss how you navigated these roles, and describe any situations that challenged the balance you’d created?

A. The secret first emerged during a time when my mom was quite sick, and my siblings and I were trying to figure out how to deal with her frequent trips to the hospital emergency room and her resulting anxiety. That initially put me in the role of son, and as a son, I believed what Mom had told her doctor and what was reported to us: That she had no idea what had happened to her sister. Of course, that turned out not to be true.

Once I set out to write a book, I wanted to tell the story fully, without holding back. I’ve been a journalist for so long that it wasn’t hard for me to slip in the role of questioner and observer. I sometimes wonder if that’s one reason why I chose journalism: It’s one of the few professions that sometimes demands immersion in difficult and emotional subjects, while allowing the reporter to set aside, or even submerge, his or her own feelings.

A book puts the writer into a more complex relationship with the material. I wanted to apply the discipline of journalism to ferret out the story, but I didn’t want to push aside my feelings—they were part of the story, too. Sometimes I found myself taking notes on my own reactions, and that felt strange at first.

Q. At some points in the narrative, I see you holding back your personal reaction to avoid influencing the person you’re interviewing. Can you talk about that?

A. The most difficult moment came when my cousin, Anna Oliwek, replayed her long-ago argument with my mom over the secret. This argument was in the early 1950s, not long after Anna emigrated to the United States and learned from older family members about Annie.

To put it bluntly, Anna had nothing but contempt for Mom’s decision to hide Annie’s existence. I didn’t want to defend Mom, but later I realized that as the reporter, as the storyteller, I had to push back if I wanted to go deeper into understanding Anna’s feelings and my mother’s motivations. As a writer, that was liberating. But it was also somewhat liberating as a son.

Q. Along the same lines, your book is a hybrid of memoir, a genre that embraces subjectivity (some say to an extreme degree), and journalism and history (which ostensibly rely on objectivity). What challenges resulted from working in these three different genres? After so many years in journalism, was it difficult to write personally, with yourself as the main character?

A. Honestly, it was more fun than difficult. Sure, there were challenges, but they were the challenges that came from trying to untangle a complicated and hidden story, not from writing in a personal voice.

When my book proposal went out to publishers, one interested editor wondered whether the story might be better told as straight history/biography, keeping myself out of it. Generally, I prefer that style, but it demands authoritativeness, and I wasn’t sure I could gather enough information to achieve that voice. I saw Annie’s Ghosts as a story about a search, about putting myself in someone else’s place, about whether the truth can be found, and how to navigate the distortions that memory imposes on the truth. It seemed natural to write the story as part memoir and part history, while separating my memories from those of the people I found and interviewed.

The book doesn’t fit neatly into any one genre, I’ve been told. That pleases me. It sounds rather appealing to be operating in the cracks between various styles. No writer minds being accused of doing something different.

One early online reviewer wrote: “It’s a true story that reads like a true story.” I loved that. Some memoirists have given the genre a shaky reputation by employing invented dialogue or scenes, saying that they help tell a larger truth. It seems to me that writers already have a genre for that approach. It’s called the novel.

Q. You put sections of personal memory into italics, as if you’re consciously trying to prevent the memoir thread from infiltrating the journalistic thread. Can you discuss the various levels and kinds of narrative at work here?

A. A writer doesn’t want to give away too many secrets! But yes, I wanted to set off the sections, to flag those as my voice, and my voice alone – and to warn readers that these vignettes come largely from memory, not from research.

Those sections, which appear throughout the book, stand as a running (and somewhat separate) narrative of my attempts to reconcile the mom I remembered and the secret keeper that I had discovered. These sections also support the theme of reinterpretation: They exist as memories, but must I now reinterpret all my memories in light of the information I’m uncovering?

Q. As you got deeper in your research, what was the biggest surprise you encountered?

A. I never thought I’d find so many secrets, with so many levels and implications—and not just in my own family. In retrospect, I’m not sure why I wasn’t prepared for that. I suppose it seems obvious that secrets beget other secrets. Chalk it up to naivety.

The difficulty of getting Annie’s records also was a surprise. I had no idea that a family member would have such trouble seeking information about someone long dead. I think we need to revisit our privacy laws, and make sure that they don’t prevent us from telling our own history.

Q. Did you worry that you wouldn’t be able to learn enough about Annie’s life to write the book?

A. In a word, yes. Like any writer, I wanted to work with the complete record of her institutionalization, to spend hours interviewing a doctor who had treated her or find an attendant who had worked on her ward. The book isn’t the story of her life, though. It’s the story of a secret and its consequences, and how that secret remained powerful. Recreating Annie’s world was crucial to telling that story, but recreating Annie’s life was not. The book has several narratives in play; removing Annie’s anonymity is one of them.

Q. You found a lot of secrets during your research. Do you think your family had more secrets than the “average family”?

A. In the book, I wrote that I’ve become a collector of other families’ secrets. It’s remarkable how many families have something hidden, a subject that everyone “knows” is not to be discussed. Every generation seems to create its own taboos, although some old ones linger on.

Today, of course, revealing family secrets has become fashionable, even a staple of TV talk shows. I interviewed Deborah Cohen, a professor at Brown, who was writing a book about the rise of the “confessional culture” in Britain. (Her book has since been published.) We had a fascinating discussion about my dual role as son and journalist, which I relate in the book.

Q. At least one of your siblings had been a bit hesitant about your quest. Do they still feel that way, now that the book is done? How do you think your family was affected by the information you uncovered?

A. As I wrote in the acknowledgments, “a secret stands at the center of Annie’s Ghosts, but a family stands behind it.” My siblings have been involved since the beginning, and I feel fortunate to have their support, which doesn’t mean that everyone sees the story the same way. The manuscript made the rounds of the family, generating a lot of discussion—which I benefited from as I worked on the revisions.

Q. Your cousin Anna Oliwek, the Holocaust survivor who argued with your mother about her secret, is such an interesting character. When did you know you would visit Radziwillow, where Anna’s family died in the Nazi-led massacre of the town’s Jewish population?

A. As one of the few people still living who had met Annie and talked with my mom about her secret, Anna became a central figure in the book in ways that I hadn’t anticipated. Her story of surviving the Holocaust, and how that shaped her worldview, made her even more compelling.

The more I interviewed her, the more I felt the pull to visit Radziwillow, to see the mass gravesite, to look for some hint of my family’s past there. I had no illusions that I would find the Radziwillow of Anna’s youth, let along the Radziwillow that my grandparents left before World War I.

Interestingly, Anna couldn’t understand why I wanted to go to Radziwillow. She associated the town, and its inhabitants, with the massacres there and the murders of her mother, brother and sister. When I called her from Ukraine to tell her what we had seen, and to ask her a few questions before our return to the town the next day, she warned me several times to be careful where I went, and whom I approached.

Perhaps that’s why it was gratifying to find people in Radziwillow whose families had sheltered Jews. I knew of the Radziwillow where Jews had been massacred—but I had no knowledge of this other Radziwillow.

Q. The book memorializes Annie in a way that was never done in life or at her death. Yet, we don’t know much about her day-to-day existence. As a reader, I found myself needing to believe that every day was not a living hell, that she did have some happiness. What about you—how did you cope with the knowledge of her suffering and loneliness?

A. I don’t know if her life was a living hell, but it was a circumscribed, unhappy and unrelenting existence, in a setting that had little to offer her. The low point for me: When I read in a 1972 hospital report, written just months before Annie’s death, that she was “incoherent and irrelevant much of the time.” How long had she been that way? Certainly not in the late 1950s when Anna was driving my grandmother to see Annie at Eloise.

I couldn’t change what happened to Annie, so I tried to focus on how someone with Annie’s disabilities would fare today. Could she work? Could she live in a group home and achieve that independence she craved?

The answers I uniformly got from experts—that, yes, she probably could make it today—gave me some small comfort that we have learned something from the suffering and loneliness that characterized Annie’s life, and the lives of others who languished in mental hospitals of the mid-20th century.

Q. This really seems like a book that tells the stories of three Jewish women during the first half of the 20th century: Annie, your mother, and Anna Oliwek. In a lot of ways, you’ve written women’s history as much as family history. What are your thoughts on that?

A. I’m pleased that you think so! I can’t claim that I set out consciously to write women’s history, or even family history. My goal was to wear the skins of every major character in the story, to understand how each of them saw the world, and to understand how the world saw them.

Annie, my mom and Anna Oliwek all represent different strands of that universal longing for freedom and its benefits. That longing, as much as secrets and secrecy, permeates the book.

RELATED CONTENT

Readers’ Discussion Guide

As a book that delves deeply into personal choices and social history, Annie’s Ghosts offers a wealth of material for book club members to discuss and debate. Here is a list of suggested questions to add to your own.

1. A secret stands at the center of Annie’s Ghosts, a secret potent enough to change lives even as it remained buried for nearly 60 years. But the book isn’t just about that secret. Steve Luxenberg has said that the book is also about freedom and identity. What do you think he meant?

2. Annie’s Ghosts revolves around three people: Steve’s mother, Beth; Steve’s secret aunt, Annie; and Steve himself, the journalist-son who pursues the secret. Why do you think the author chose “Annie’s Ghosts” as the title rather than “Beth’s Ghosts”? Why does the title refer to multiple ghosts rather than to a single ghost

3. Learning about Annie forces Steve to abandon his image of his mother’s childhood. He finds this hard. “In my mind’s eye of life on Euclid, I had no space for Annie, no idea of where she fit,” he writes (p. 17). What importance do you place on what your parents told you of their younger selves?

4. At the end of Chapter One, Steve describes his relationship with his mother as close. Pursuing Beth’s secret, he says, wasn’t a way “to settle any scores or revisit old arguments” (p. 25). Does Steve succeed in remaining non-judgmental in his quest to understand his mother’s motivations? Do you think it’s possible to be non-judgmental when it comes to writing about one’s own family?

5. Social worker Mona Evans, describing Annie’s mother, Tillie, wrote in a 1940 report: “She is a poorly dressed, middle-aged Jewish woman. She talks in a complaining, whining voice, expressing a great amount of antagonism toward the Welfare, various hospitals, etc.” (p. 45). Discuss how and why Tillie might have felt this way. Did her immigrant status shape her views? If so, how?

6. As Steve pursues the secret, he finds people are eager to tell him the hidden stories of their families. He calls himself a “collector of other families’ secrets” (p. 47). How and when do you think it is appropriate to tell a secret? Which secrets are better not revealed? Do you think Steve would have written Annie’s Ghostsif Beth were still alive?

7. Steve calls Annie’s Ghosts part memoir, part history and part detective story. The book doesn’t fit neatly into any one of the traditional nonfiction genres. How does the book differ from other memoirs you have read?

8. Steve and his brother Mike don’t agree on pursuing the secret. Mike tells Steve he doesn’t understand Steve’s quest. “We can’t stand in their shoes,” he says (p. 105). He also warns Steve that digging into the past might lead to other secrets, and asks Steve whether he is prepared for what he might uncover. Would you want to know more about a family secret if one came out? How would your family react?

9. Steve sprinkles the narrative with multiple memories of his parents, always in italics. Several themes and emotions pervade these vignettes. Discuss how these vignettes add to the portrait of Beth and Jack. How does the author try to establish the trustworthiness of his recollections? Why does it matter in this particular story?

10. Beth and her cousin Anna Oliwek, a Holocaust survivor, argue about the secret sometime in the early 1950s. Steve’s attempts to understand each woman’s point of view enmeshed him in Anna’s story of pretending to be German and getting a job as a translator for the Wehrmacht during World War II. Do you reject Beth’s decision to hide her sister’s existence, as Anna does, or do you see her more sympathetically? What would you have done if you were in Beth’s shoes, at that time and in that place?

11. The nature of memory is a recurring theme in the book. For example, in recounting his frustrations in interviewing Anna Oliwek about the details of her argument with Beth, Steve writes: “Those nuances lie beyond my reach. I cannot wrest them, undistilled or unvarnished, from Anna’s memory” (p. 131). What do you think he means? Why is that important?

12. Annie’s 31 years at Eloise span two strikingly different eras in the treatment of the mentally ill. In 1940, the state of Michigan viewed treatment as an obligation, but patients had few rights; today, patients generally cannot be forced into treatment if they object, but serious mental illness goes untreated more often. Discuss the tension between care and civil liberties. Have we struck the right balance with today’s laws?

13. Hospital records provide the only way for readers to hear Annie’s voice, and the author has only a small portion of those. Steve writes (p. 212) that he tries to “inhabit Annie’s world” through interviews and visits to places where she spent time, including her school. How does Annie’s anonymity change the nature of the storytelling?

14. Changes in federal and state laws over the past 25 years have emphasized privacy over disclosure, in part to protect living patients from abuse and discrimination. That trend puts obstacles in the way of telling stories like Annie’s. Have we gone too far in protecting the privacy of patients long dead? Discuss the conflict between privacy and history.

15. Gravesites serve as an important continuing locale in the story. What is the relationship between the Jews killed in the Radzivilov massacres during World War II and the former residents of Eloise Hospitals buried in the potter’s field. What role do the three burial sites in Annie’s Ghosts play in preserving or obscuring identity?

16. An online reviewer observed that the book “is not a true story that reads like fiction (a description that has fallen under suspicion these days), but is, in the best sense, a true story that reads like a true story.” What do you think she meant? Do you agree?

Behind the Book: A Detective Story

Names.

Column after column of names from the past, from the 1930s, from the streets that my mom called home while growing up in Depression-era Detroit. I stared at the microfilm in the subdued light of the National Archives reading room, a time traveler to my mother’s teenage life, looking for names of her friends or classmates.

I didn’t recognize a single one.

To understand my mother’s reasons for hiding her sister’s existence, to learn as much as I could about my secret aunt, I was trying to reconstruct the world as Mom and Annie knew it in 1940, the year of Annie’s institutionalization for mental illness at Eloise Hospital outside Detroit. To see what Mom saw, I had to find the people who lived in her apartment building, or went to her school, or listened to her account of what had happened.

Mom couldn’t help. When she died in 1999, she left behind almost nothing that hinted at the secret she kept for nearly 60 years. Like any mystery, the story that would become Annie’s Ghosts had to be pieced together, bit by bit. City directories yielded a list of neighbors, and school yearbooks gave me the names of classmates, but could I find them? Were any still alive? Did they know about Annie’s condition? Had they talked to Mom or Annie? Would they remember what they said?

Clues rarely came to light in a neat or sequential way. Many paths led to dead ends, while others led to obituaries confirming that Mom’s generation was rapidly shrinking in numbers. Slowly, however, a picture came into view, much like the paint-by-number canvasses that Mom lovingly labored over in the 1960s.

The book tells that story. Here, I have included a visual narrative of photos and documents that go beyond the words and images that appear in Annie’s Ghosts.

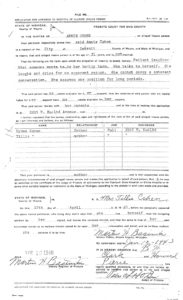

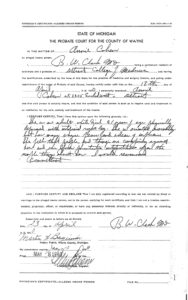

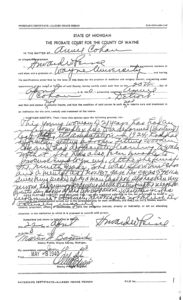

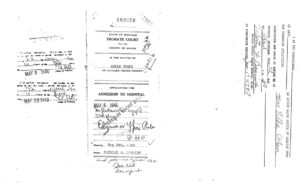

Annie’s Court File

In April 1940, at the suggestion of a doctor at Harper Hospital in Detroit, my grandmother filed a petition in the Wayne County Probate Court, alleging that her daughter was insane. Two weeks later, a judge sent Annie to Eloise Hospital on a temporary detention. The doctors who examined Annie reached different conclusions about whether she would benefit from confinement and treatment at Eloise, a county facilty for the mentally ill.

Click any image below to read the court records.

Radziwillow and the Holocaust in Ukraine

The town of Radziwillow, now part of western Ukraine, plays a prominent role in Annie’s Ghosts. My grandparents both left Radziwillow before World War I, emigrating to the United States. A cousin, Anna Oliwek, was eighteen years old when a Nazi-led killing squad massacred 1,500 Jews there in May 1942, including Anna’s mother, sister and brother.

Anna’s account of how she survived the Holocaust is a remarkable one. An excerpt that tells her story appeared in The Washington Post Magazine on March 15, 2009.

When Anna came to Detroit after the war, she learned of my mother’s secret and could not accept the idea that Mom was hiding the existence of a living relative. They argued, and that led to a falling out that they never repaired. After meeting Anna in 2006, I visited Radziwillow so I could better understand her views.

See photos of the mass gravesite, the town, and Anna below.

Photos by Mary Jo Kirschman, unless noted.

The Power of Family Secrets

Below is a gallery of photos and documents, including several not found in the book, that helped me piece together the story of Annie’s Ghosts.

My mother, the secret keeper, appears in a photograph with my father. The woman in the tattered photo is my grandmother. (I never found a photo of Annie.)

Except where noted, the images come from the Luxenberg family collection.