Separate

The Story of Plessy v. Ferguson, and America’s Journey from Slavery to Segregation

A myth-shattering narrative of how a nation embraced “separation” and its pernicious consequences.

Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court case synonymous with “separate but equal,” created remarkably little stir when the justices announced their near-unanimous decision on May 18, 1896. Yet it is one of the most compelling and dramatic stories of the nineteenth century, whose outcome embraced and protected segregation, and whose reverberations are still felt into the twenty-first.

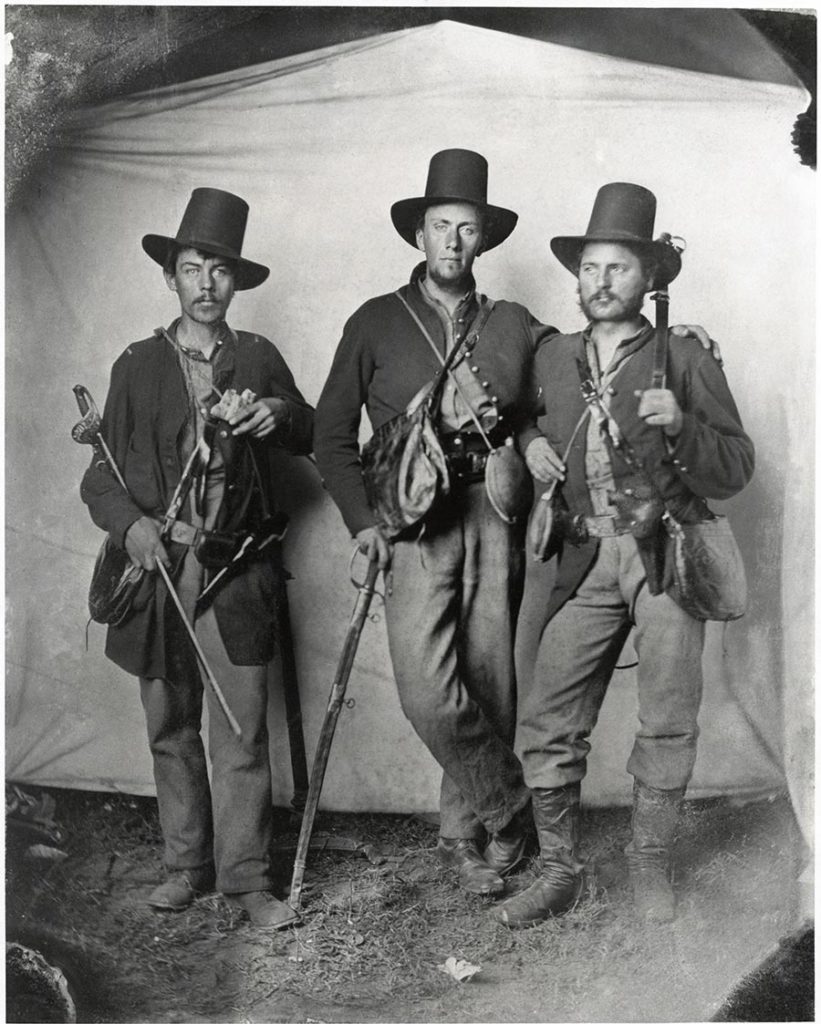

Separate spans a striking range of characters and landscapes, bound together by the defining issue of their time and ours—race and equality. Wending its way through a half-century of American history, the narrative begins at the dawn of the railroad age, in the North, home to the nation’s first separate railroad car, then moves briskly through slavery and the Civil War to Reconstruction and its aftermath, as separation took root in nearly every aspect of American life.

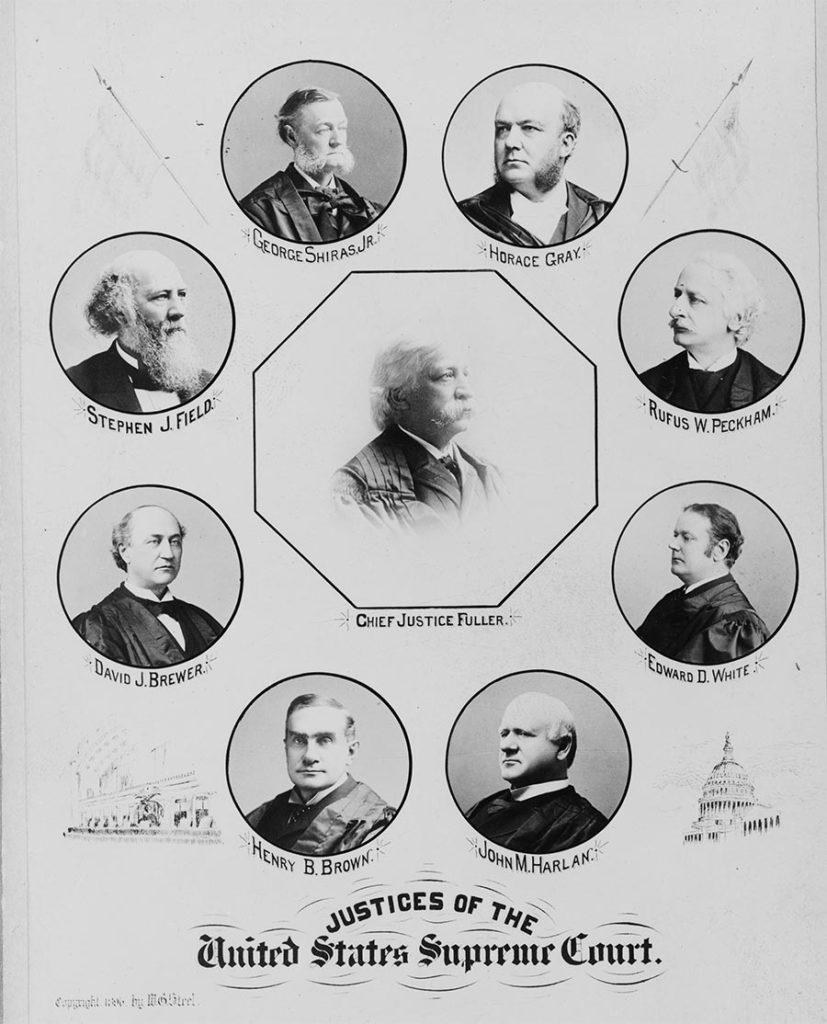

Award-winning author Steve Luxenberg draws from letters, diaries, and archival collections to tell the story of Plessy v. Ferguson through the eyes of the people caught up in the case. Separate depicts indelible figures such as the resisters from the mixed-race community of French New Orleans, led by Louis Martinet, a lawyer and crusading newspaper editor; Homer Plessy’s lawyer, Albion Tourgée, a best-selling author and the country’s best-known white advocate for civil rights; Justice Henry Billings Brown, from antislavery New England, whose majority ruling endorsed separation; and Justice John Harlan, the Southerner from a slaveholding family whose singular dissent cemented his reputation as a steadfast voice for justice.

Sweeping, swiftly paced, and richly detailed, Separate provides a fresh and urgently-needed exploration of our nation’s most devastating divide.

Praise & Reviews

“Absorbing … Segregation is not one story but many. Luxenberg has written his with energy, elegance and a heart aching for a world without it.” —James Goodman, The New York Times

“Luxenberg has chosen a fresh way to tell the story of Plessy. . . . Separate is deeply researched, and it wears its learning lightly. It’s a storytelling kind of book. . . . Luxenberg skillfully works the military and the political background into his narrative.”

—Louis Menand, New Yorker

“A dazzlingly well-reported chronicle of an important period. . . . Luxenberg repeatedly manages to tell us stories that capture both the hope and hopelessness that has been central to America’s long argument about race. . . . An eye-opening journey through some of the darkest passages and haunting corridors of American history.”

—Terence Samuel, NPR

“Luxenberg gives a three-dimensional and almost novelistic treatment to the players involved, drawing on diaries, letters and archival research.”

—Joumana Khatib, The New York Times

“Luxenberg writes at the outset of his book that the story of Plessy is a reminder that ‘history is made, not ordained.” In his moving portrait of the many figures who played a role in the case, he confirms that idea as well as another: that even the most hopeless fool’s errand can emerge, in time, as an unassailable triumph.”

—Charles Dameron, The Wall Street Journal

In Separate, the context and aftermath of the court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson are woven into a nuanced history of America’s struggles in the 19th century as a civil war was fought, slavery ended and a new, complex racial politics haltingly took form. . . . Like any good history, Separate introduces some puzzles while resolving others.”

—The Economist

“[Luxenberg] is a fine writer who tells this story in an engaging manner. . . . Separate reminds us that our history is not simply a narrative of greater and greater freedom.”

—Eric Foner, The Washington Post

“Luxenberg has written an ambitious and deeply researched nonfiction account [that] draws on letters, diaries and archival collections to being this true story to life.”

—Suzanne Van Atten, Atlanta Journal Constitution

“A surprising, compelling, and brilliant milestone in understanding the history of race relations in America.”

—Bob Woodward, author of Fear: Trump in the White House

“Riveting and deeply researched, Separate tells the story surrounding one of the nation’s most devastating acts: drawing a sharp color line between black and white after the Civil War. The Plessy case was a knife that cleaved America, and Steve Luxenberg brilliantly reveals that divide with his rich narrative of admirable and flawed characters caught in the battle over racial justice. Every paragraph resonates in today’s headlines.”

—Walter Isaacson, author of Steve Jobs, and professor of history, Tulane University

“Forensically researched, deeply moving, devastatingly relevant.”

—Katherine Boo, author of Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity

“This is a compulsively readable work of serious history, the absorbing and timely story of a disastrous U.S. Supreme Court decision, freshly told through the lives of those directly involved. Steve Luxenberg’s scholarship is deep and impressive; his writing even more so. This is history as it was lived, giving us a sense not only of the deep racism of the period, but the struggle of decent men and women to overcome it, in society and, most importantly, in themselves.” —Mark Bowden, author of Black Hawk Down and Hue 1968: A Turning Point in the American War in Vietnam

“Plessy v. Ferguson looms large in American history, and it remains searingly relevant today, but it is ill understood. Steve Luxenberg uses his relentless reporting skills and keen narrative expertise to reveal the full story. His uniquely valuable book will appeal to fans of Ron Chernow’s Grant and Doris Kearns Goodwin’s The Bully Pulpit—and to anyone who wants to understand how America’s current racial landscape came to be.”

—Garrett Epps, professor of law, University of Baltimore, and author of Democracy Reborn: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Fight for Equal Rights in Post-Civil War America

“At this critical moment in our nation’s struggle for racial justice, Steve Luxenberg’s Separate provides a compelling picture of an earlier stage in that quest. Unlike Gideon’s Trumpet or Simple Justice, his story does not end with a judicial triumph. But in viewing Plessy v. Ferguson through the lives of its protagonists―the plaintiff, his sponsors, his lawyer, the Justices who decided the case―he reminds us that the pursuit of justice comes down to individuals, not just institutions. He has written a fascinating, if sobering volume.”

―Peter M. Shane, professor of law, the Ohio State University

“Steve Luxenberg’s interwoven narrative takes the story in a new direction, providing illuminating answers to fundamental questions. . . . A rich, complex, and all too human story, replete with ironies and unintended consequences. This is ‘big history,’ deeply researched and well-told.”

—from the J. Anthony Lukas Award Citation

“In lucid prose, Luxenberg lays out the history of racialized segregation in the North and South of the United States and offers vivid portraits of main actors in this civil rights struggle.” —Publishers Weekly

“Luxenberg brilliantly tackles a difficult task, presenting his solidly researched work clearly and with a restrained objectivity. . . . An engaging and sensitive exploration of America’s detour from the promise of equal protection.”

—Kirkus, starred review

“In documenting this country’s fateful journey from slavery through thwarted Reconstruction to segregation, Luxenberg paints on a broad canvas, elegantly narrating several captivating and scrupulously researched stories that converge in Plessy v. Ferguson.”

―Steve Nathans-Kelly, The New York Journal of Books

“The reader’s delight is to follow Luxenberg as he intertwines [several] stories from widely singular strands at the beginning to their historical moment on the stage together in 1896. . . . a monumental work.”

—Y.S. Fing, The Washington Independent Review of Books

“. . . a work of impressive scope, depth and sensitivity . . .”.”

—Harvey Freedenberg, bookreporter.com

“A masterly narrative. . . . In the sweeping style of Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, this work will be enthusiastically received by informed readers and historians and is likely to become the seminal work on this crucial Supreme Court decision.” —Library Journal, starred review

Cast of Characters

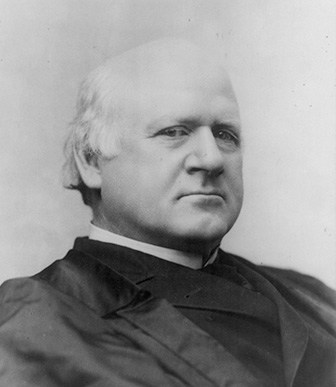

Henry Billings Brown, author of the majority opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson. Born in Massachusetts, 1836; moved to Michigan, 1859.

John Marshall Harlan, the only dissenter in Plessy v. Ferguson. Born in Kentucky, 1833.

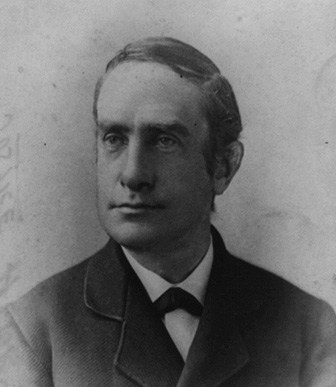

Albion W. Tourgée, recruited to argue Plessy, also a best-selling author and weekly newspaper columnist for the Chicago Inter Ocean. Born in Ohio, 1838; moved to North Carolina, 1865; returned to the North, 1879.

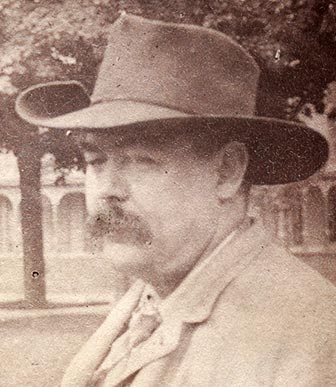

Louis A. Martinet, editor of the New Orleans Crusader and guiding force behind the Citizens’ Committee to Challenge the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law, also known as the Comité des Citoyens, reflecting the group’s French Creole leadership. Born in Louisiana, 1849.

Caroline (Pitts) Brown, first wife of Henry Billings Brown. Born in Michigan, 1844.

Malvina (Shanklin) Harlan, wife of John Marshall Harlan. Born in Indiana, 1839.

Emma (Kilborn) Tourgée, wife of Albion Tourgée. Born in Ohio, 1840.

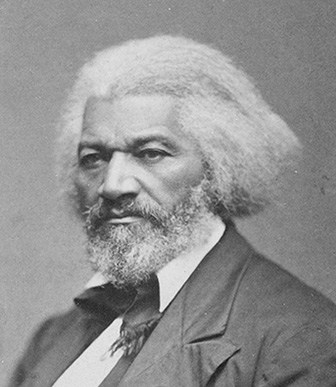

Frederick Douglass, abolitionist, orator, author. Among the first passengers of color to be ejected from a railroad car for sitting in seats reserved for whites. Born in Maryland about 1817. Fled from slavery in 1838.

Rodolphe L. Desdunes, member of the Citizens’ Committee and a contributing writer to The Crusader. Born in Louisiana, 1849.

Daniel Desdunes, chosen by the Citizens’ Committee to test the separate car law, arrested by arrangement in February 1892. Son of Rodolphe Desdunes. Born in Louisiana, about 1870.

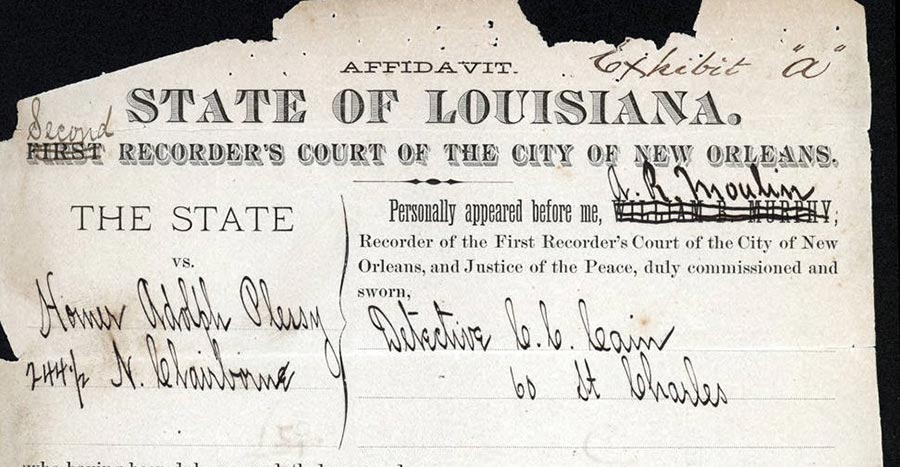

Homer Plessy, chosen by the Citizens’ Committee to test the law, arrested by arrangement in June 1892. Born in Louisiana, 1862.

John H. Ferguson, the state judge whose rulings were appealed by Plessy’s team, making him the defendant in Plessy v. Ferguson. Born in Massachusetts, 1838; moved to New Orleans, 1866.

James C. Walker, a white New Orleans lawyer hired by the Citizens’ Committee to work with Tourgée and act as local counsel. Born in Louisiana, 1837; served in the Confederate Army.

Audio Excerpt of the Prologue

Prologue

April 1896

At his spacious home in the quiet town of Mayville, nestled in the farthest corner of western New York State, Albion Tourgée looked at his co-counsel’s two-page letter with disbelief. “There is some chance that the case will be argued tomorrow,” read the message from Washington.

What? Tomorrow?

Tourgée glanced again at the date on the letter: April 1, 1896. Tomorrow?

There was no tomorrow. It was Friday, April 3. Tomorrow was now yesterday. If the oral arguments in the Supreme Court lawsuit known as Plessy v. Ferguson had taken place the day before, then Tourgée had missed perhaps the most important oration of his career, one he had spent more than three years preparing to give.

Impossible. Outrageous. Unforgivable.

Cold fury could be felt in every word of his hurriedly composed note to the Supreme Court clerk’s office—an icy, personal anger built upon three decades of disappointment with the North of his birth and its failure to erect a citadel of civil rights from the ashes of the Civil War. “I have been ready for the hearing for three months, waiting every day to know when it would probably be reached,” he thundered, “but have never heard a word from you.”

With a characteristic flush of hyperbole, he rushed on. “I represent an association of about 10,000 colored men of Louisiana who raised the money to prosecute these and other cases, and now by some inscrutable mishap they are deprived of the service they had secured.”

He was fifty- seven years old, with a glass eye to replace the one blinded in a boyhood gun accident. As perhaps the nation’s most famous white advocate for civil rights, he had lived much of his tumultuous life on the outside looking in, and he had a well- deserved reputation for not suffering fools easily.

The accent mark in his last name was a Tourgée invention, adopted in his mid- forties, reflecting a personality often characterized by emphasis and embroidery. He was most comfortable on a podium exhorting a crowd, or at his writing table crafting a novel or drafting his newspaper column, rather than socializing in the drawing rooms of New York or Washington. He had gone South after the war, seeking to cement the revolution. When he left after fifteen years of fighting with the established order, some had cheered. One newspaper, bidding him farewell, called him the most hated man in North Carolina. In white supremacist circles, the label might not have been an exaggeration.

His Supreme Court experience could be summed up in half a sentence: two minor cases, twenty- five years ago. He was unfamiliar with the court’s practice of notifying only the local counsel about the scheduling of a case. The “inscrutable mishap” turned out to be mostly his co- counsel’s fault. He had known for several days that Plessy had been assigned a place in the court’s queue for oral arguments, but he had failed to alert Tourgée right away.

Mystifying. Astonishing. Maddening.

Fortunately, as Tourgée soon learned from court clerk James McKenney’s courteous reply, the justices hadn’t reached as many cases as expected before adjourning for a week’s recess. Plessy was next in line. The probable date now: Monday, April 13, plenty of time for Tourgée to get there. The location: the Old Senate Chamber, the Supreme Court’s home since 1860. Plessy would not go forward without its architect in chief.

TOURGÉE HAD NURTURED the Plessy case with the care of a horticulturist tending a prized set of orchids. But his involvement was more chance than destiny.

Nearly five years earlier, in the summer of 1891, he had written a particularly acid newspaper column denouncing the new “separate car law” in Louisiana, which mandated “equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored passengers” traveling on trains in the state. His column had acted like a shot of adrenaline for a committee of prominent mixed- race Creoles and several black allies in New Orleans, which was already bent on mounting a legal challenge to the law. At the committee’s invitation, Tourgée had assumed command of the case, working with lawyers in New Orleans and later Washington. The committee’s leaders couldn’t believe their good fortune in having a man of Tourgée’s stature on their side. Even better, he had refused to take a fee for his service. For Tourgée, this was more than a case. This was the culmination of a three-decades-long crusade to build a society that paid more than lip service to equal rights.

On Friday, April 10, he boarded the train for Washington, with hours ahead of him to review his arguments. He had done more than anticipate this moment. He had planned for it, imagined it, played out the scene over and over in his mind’s eye, calibrating and recalibrating every detail. His fame drew attention to the case, but it also brought its own baggage. When it came time for his oral argument, the justices would not be looking at a lawyer with a legal claim. They would see a rebel with a cause, a man who had warned in his writings that the country should prepare for a race war if it did not address the wrongs visited every day on people of color.

As an accomplished orator, Tourgée thought he knew how to read an audience. He had studied the nine Supreme Court justices, looking for any advantage, any clue that would help him and his colleagues in constructing a winning argument. He had urged the New Orleans committee to find his ideal candidate for arrest, a man of mixed race who looked white, could pass for white, who could take a seat in a car reserved for whites and throw doubt on the ability of any train conductor to guess the passenger’s race by sight. The Louisiana law essentially required the railroad to decide the race of each passenger. What if the conductor couldn’t tell?

That scenario would create the most favorable circumstances for his argument. He intended to prove that the separate car law not only violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection for everyone within a state’s jurisdiction, but that it was unenforceable as well. Tourgée wanted to do more than impress the justices with his logic. He wanted to open their eyes to the inherent contradictions of previous rulings. He wanted to show them the errors in the court’s interpretations of the three constitutional amendments enacted after the Civil War to ensure equality. He wanted a triumph.

THE ONLY SURE VOTE, in Tourgée’s estimation, was Justice John Marshall Harlan of Kentucky, a slave owner’s son and the inheritor of his family’s slaves. Despite that background, Harlan’s dissents in previous civil rights cases had been noteworthy for their plainspoken language about the dangers of discrimination and inequality. But Harlan was usually alone in his dissents. Was it possible for him to bring others along this time?

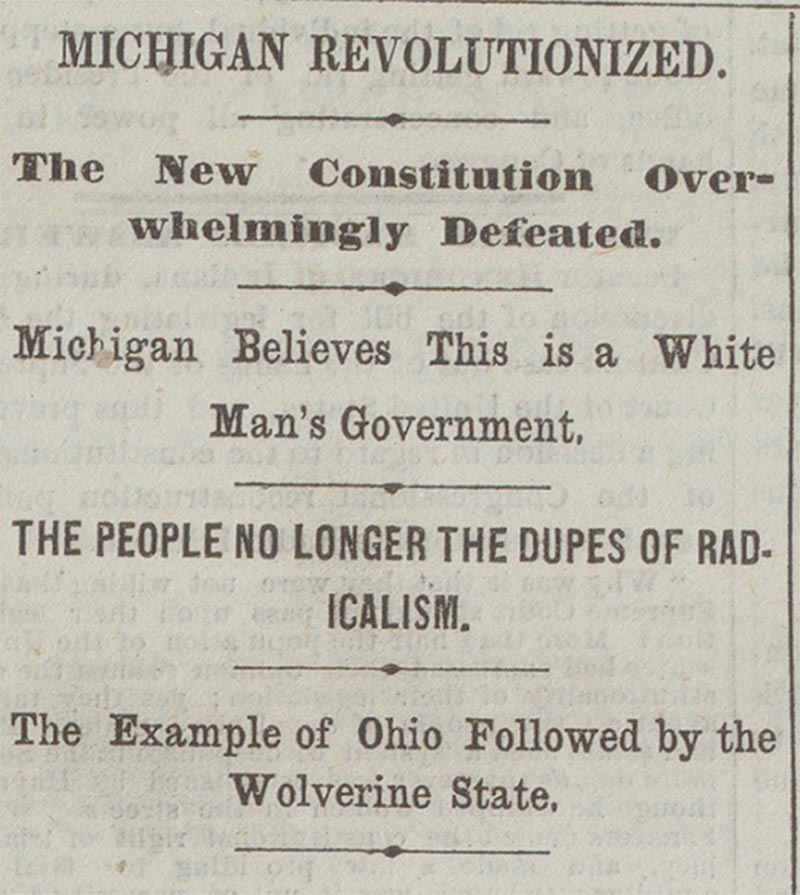

Seven of the other eight justices hailed from the North, including several New Englanders who had joined the court since its last major civil rights ruling in 1889. Was it too much to hope that newcomers Henry Billings Brown and his Yale classmate, David Brewer, might form the nucleus of a group more sympathetic to racial equality than their predecessors had been? Both had roots in western Massachusetts, where their families had raised them with an emphasis on tolerance. Both were Republican appointees, and the party still took some pride in its antislavery roots. Both had moved west as young lawyers, Brewer to the Kansas frontier, Brown to Michigan. Their previous writings suggested no resolute position on racial equality. Brown, in particular, had a reputation for an open mind and impartiality.

Tourgée needed more than their votes. He needed them to embrace his arguments. When the justices eventually met in private to discuss the case, he needed someone other than the dependable Harlan to become spokesmen for his cause. Only then would he have any hope of persuading the court’s Northerners that this case was different, that separate was not equal, could never be equal—at least not when a Southern legislature was deploying a law to promote the desires and interests of one race at the expense of another.

Taking the case to the Supreme Court was a risk, as Tourgée knew all too well. Defeat could mean an endorsement of separation that would be difficult to undo. “It is of the utmost consequence that we should not have a decision against us,” Tourgée had written in October 1893 to Louis A. Martinet, the committee’s most active leader and the editor of the New Orleans Crusader, a newspaper that had built a following in the city’s Creole and black neighborhoods.

Without Martinet, there likely would have been no case, no fundraising, no sustained protest of the legislature’s infernal vote to enshrine separation into Louisiana law. Martinet was unflagging. He griped to Tourgée that the committee had thrown all the work on his slight shoulders, but it was the good- natured complaint of an energetic campaigner drawing on a seemingly bottomless reservoir of anger and purpose. As a man of mixed race who could pass for white, and often did, Martinet did not feel the sting of separation as strongly as others in New Orleans. But he had no doubt about its evil effects. “To live always under this feeling of restraint is worse than living behind prison bars,” he wrote to Tourgée.

Over the course of the case, the two men had developed a strong personal relationship, exchanging lengthy, often anguished letters about the state of racial inequality in the country. Their similarities stood out more than their differences. Both were men of ego, inclined toward action, yet consumed by misgivings about their mission. Both felt, often, like outcasts. Both were impetuous. Both believed that separation mocked the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection.

Perhaps most of all, both found a good fight hard to resist.

SUPREME COURT CASES often arise out of the ordinary friction of everyday life. Not Plessy. It had been a prearranged arrest, the second of two such test cases, both engineered by the New Orleans group that had adopted a name as straightforward as its cause: the Citizens’ Committee to Challenge the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law, or the Comité des Citoyens in French. The railroads had agreed to participate in the ruse, eager to settle the constitutional question before spending a lot of money on extra cars. Which is how Homer Plessy ended up at the New Orleans Press Street depot on June 7, 1892. He was twenty- nine years old, married, and fair- skinned enough to cause confusion. In his neighborhood of Faubourg Tremé, a favorite of the French- speaking free people of color, les gens de couleur libres, he blended right in.

It was no accident that the Plessy case emerged from the mixed- race culture of New Orleans, a city unlike any other in the United States in 1890. The French- speaking Creoles felt particularly aggrieved by their loss of status after the Civil War. Many had wealth, education, and a strong motivation not to slip farther on the social scale. If the case had come from any other city, it’s unlikely that a man who looked white would have been sent to buy a ticket for the whites-only car.

But then, Plessy occupies a peculiar place in the American narrative on race. It’s safe to say that many people recognize the case as a famous one, and many can place it as the one that sanctioned the “separate but equal” doctrine. But ask about even the basic facts, and the likely reaction is a blank stare. They don’t know that the case is one steeped in contradictions, or that it arose from a very public discussion about race, or that there were plenty of advocates working in opposition to the forces of racial injustice.

Just like the people swept up in the case, the story behind Plessy is neither plain nor simple. It sprawls and snakes through almost a century of American history, beginning at the dawn of the railroad age in the North, germinating in the soil of slavery and the Civil War, sprouting in the turmoil and tension of Reconstruction, and then bursting forth at the end of the nineteenth century as separation took root in nearly every aspect of American life.

The ruling in Plessy drew little attention at the time, but its baneful effects lasted longer than any other civil rights decision in American history. It gave legal cover to an increasingly pernicious series of discriminatory laws in the first half of the twentieth century. Under the banner of keeping the races apart, much of white America stood silent as black Americans suffered beatings, assaults, and murders. Lynching, already a weapon of vengeance and vigilante justice in the years before the Plessy decision, became a signature tool for whites bent on domination and repression. This culture of violence flourished, primarily but not exclusively in the South, because some proponents of separation embraced the twisted notion that enforcing laws of racial separation had a higher priority than liberty, justice, fairness, or opportunity.

The Plessy case underscores a central fact about the Supreme Court: Its decisions cannot be viewed in isolation. They follow a string of earlier rulings, and they precede a fresh set of issues that can sometimes be foreseen but never guaranteed. Questions about racial equality confronted the country’s founders, who embedded their divisions into the Constitution in 1789. We grapple with those questions still, in every new dispute involving voting rights and immigration, affirmative action and school funding, criminal justice and capital punishment.

All Supreme Court stories have their own geography. Remarkable characters populate the landscape of this one: Tourgée of Ohio, Brown of New England, Harlan of Kentucky, Martinet of Louisiana, on separate paths to a shared destination, connected by time, culture, happenstance, and the unresolved struggle between an exhausted North and a bitter South.

Their actions and attitudes, their flaws and foibles—who they were, where they lived, what they said, why they said it, how their views evolved during a tumultuous half century of strife and conflict—serve as powerful reminders that history is made, not ordained.

© Steve Luxenberg, 2019

Q&A

Q. Other books tell the story of the Plessy case. What’s new about this one?

A. I’m glad you started with an easy question.

Q. Isn’t that what readers want to know?

A. Yes, of course! So many choices out there. Plessy is one of the most famous Supreme Court cases in our history, but one that we don’t like to talk about, because it helped usher in a sixty-year period of legal separation by color and race. Separate railroad cars and separate schools became separate bathrooms and separate water fountains. Separate entrances to public buildings. Separate places to shop and eat a meal. Mostly in the South, but also in the North. How could this happen?

The “untold story” has become a cliché in the publishing industry. It’s not a phrase that I would use. Historians and constitutional scholars certainly have written about the case, particularly the legal ramifications. But Separate takes on the greater challenge of telling the story through multiple characters, multiple eras, and multiple locations, with the goal of illuminating the debate over slavery, separation and equal rights that dominated the national conversation for much of the Nineteenth Century. As one advance reader told me, “I studied Plessy in law school, and I thought I knew a fair amount about the case. Separate revealed how little I knew.”

Q. Why do you say “separation,” rather than segregation?

A. Here’s what I discovered: Segregation is a Twentieth Century word. Separation is the word I found in newspapers, in political debate, in letters and everyday conversation. I tell the story through the eyes of the people who eventually become caught up in the case, so I try to stick to the language they would have used.

Various forms of separation existed for decades before the Plessy case was decided in 1896. But it was a custom, not a law. Then, in 1889, the Mississippi legislature mandated that railroads must operate separate cars in the state. Louisiana followed suit a year later. Resisters in New Orleans set about devising a test case.

Q. It sounds like the book is about a lot more than the Plessy case. How did you organize a narrative that extends over fifty years and pulls in so many characters?

A. That’s why the subtitle has two parts! This book is “the story of Plessy v. Ferguson,” but it’s very much in the context of “America’s journey from slavery to segregation.”

I’m not a legal scholar, or a constitutional historian. I’m a storyteller with a passion for narrative history. Structuring the story around four main characters gave me plenty of room to move between people and places. The geography of Separate is incredibly important. So is the Civil War, which shaped all the characters in the book.

The Nineteenth Century was defined by the division between North and South, and the four characters and their families live on both sides of that divide. Henry Brown, the justice from New England and Michigan who writes the infamous Plessy ruling; John Marshall Harlan, the dissenting justice from Kentucky, where he once owned slaves; Albion Tourgée, the lawyer for Plessy, Ohio-born but battle-hardened by his years in Reconstruction-era North Carolina; Louis Martinet of New Orleans, the primary engine behind the Plessy case.

As I write in the Prologue, we meet them on their “separate paths to a shared destination, connected by time, culture, happenstance, and the unresolved struggle between an exhausted North and a bitter South.” It’s quite a journey, and I’m hoping readers will find it as compelling as I did.

Q. New Orleans is sort of a character, too, right?

A. Yes, very much so. It’s no accident that the Plessy case comes out of New Orleans. In the late Nineteenth Century, no other city in the country could claim such a wealthy, educated, and militant group of people of color. That’s because many in the mixed-race community in New Orleans, the Creoles of color, had never been enslaved. They and their ancestors had been free at the time of the American takeover. They had been agitating for equal rights for a long time, and their anger had been building. The Plessy case had its origins in the events of 1803, 1815, 1863, and 1867. Separate pulls that thread through the narrative.

Q. So it’s primarily a book about the South?

A. Not by a long shot. Separation has its roots in the North, before the Civil War. That’s where the country’s free blacks lived. When passenger railroads opened for business in the late 1830s, a new question arose for the companies and its customers: Where do I sit?

No existing form of transportation quite compared to a railroad car’s opportunities for throwing together passengers without regard for status or social group. There weren’t many people of color in the North, and few had the means or need to ride the railroads. But three train companies in Massachusetts insisted on having separate cars anyway. Five did not, proving that there was no consensus on this question of where people should sit.

Q. Only three of the early Massachusetts railroads chose to run separate cars? How did they justify that?

A. They said their customers wanted them. But abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and a young Frederick Douglass were riding those trains, going to their antislavery meetings, and as you can imagine, they saw an opportunity. They made a huge ruckus about this blatant discrimination. Which is all in Chapter One, along with the early origins of the phrase “Jim Crow.” I’m going to stop there. This Q&A is supposed to be a teaser, not a summary! But I can tell you, it’s a fascinating part of the story.

Q. What other surprises did you find?

A. We hear the phrase “civil rights,” and we immediately think of the 1960s. That’s understandable. It’s justified. The people who fought for equal rights in that era, many of them, were heroic.

But they weren’t the first. A black abolitionist went to court in 1841, in Massachusetts, to prosecute charges against a train crew that threw him off a train. He lost, but that didn’t deter others from picking up the cause. In 1855, in Michigan, William Day sued a steamboat that had refused to sell him a ticket for an inside cabin, saying those quarters were for whites only. In 1867, in New Orleans, William Nichols touched off days of protests when he insisted on boarding a white-only streetcar. That same year, in Pennsylvania, Mary Miles was in a legal fight with a railroad for ejecting her from the whites-only car. How they (and other resisters) fared in their battles is an important prelude to the Plessy test case of the 1890s.

Q. So resistance, civil disobedience and test cases aren’t Twentieth Century inventions. Anything else?

A. Something else that might surprise readers: The 1964 Civil Rights Act also had its predecessors. Three of them, to be exact, enacted in the decade after the Civil War. Those earlier laws were astounding in their scope, and in their understanding of discrimination’s consequences.

The 1866 act allowed the federal government to intervene if a state refused to investigate or prosecute acts of violence directed at people of color. The 1875 act required that “all persons,” regardless of their race or color, were “entitled to full and equal enjoyment” of public accommodations. But the laws were derailed by white supremacists pushing back, weak politicians caving in, and a series of Supreme Court rulings that began almost two decades before Plessy showed up on the court’s docket.

Q. Is there a reason why it’s important to revisit the Plessy case now?

A. I like what biographer Walter Isaacson said in his blurb praising the book, “Every paragraph resonates in today’s headlines.” Perhaps not every paragraph, but many of the questions facing us today are embedded in Separate. That’s true, I think, of every good book about history, and I hope it’s true of mine.

After the events of Charlottesville in 2017, with white supremacists descending on the city and one of their number using a car as a weapon, driving into a crowd and killing a protester, I thought of their predecessors in the 1870s, and how their fears and anger led them to violence.

Q. Is the Plessy case one of the court’s worst moments?

A. I think so, but at the time, the ruling was no surprise. The press didn’t give it big coverage, mostly because the court had already accepted separation in its 1890 ruling upholding Mississippi’s separate car law. Plessy took on greater importance after the Supreme Court reversed itself in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, saying separate is inherently unequal and singling out Plessy as the court’s wrong turn. The language in Brown permanently changed our view of Plessy, characterizing it as the case in which the court had “announced” the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

It’s important that we understand Plessy in its own time. Several times a week, I get a “Google Alert” about an article mentioning Plessy. Frequently, it’s a secondary reference about how wrong things can go—“as the Supreme Court did in the Plessy case. . .” Just as frequently, the case is described something like this: “The Supreme Court established the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ in Plessy v. Ferguson, making it the law of land.” That’s so interesting, because the court’s majority ruling didn’t do that, and no one living at that time thought it had.

The court ruled, 7 to 1, that Louisiana’s legislature, employing its “police powers” to preserve order, could enact a separate car law. Doing so, the 1896 court said, did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s promise of equal protection. The words “separate but equal” don’t appear in the majority’s ruling, and the court didn’t decree that the doctrine was now “the law of the land.” Each state could follow Louisiana’s lead, and adopt laws mandating separation. Many did. Many did not.

What shorthand would I use? I would say the Supreme Court “endorsed” or “sanctioned” the idea that separate could be equal. Why does the wording matter? Because saying that the court “established the doctrine,” in my view, lets the rest of the country off the hook. It lays separation, and its pernicious consequences in the Twentieth Century, at the feet of those seven justices.

All but one were Northerners, by the way. They were followers, not leaders. I don’t excuse them. They could have prevented the insidious spread of bigotry. They didn’t. Among the justices, only Harlan of Kentucky, a Southerner and inheritor of his family’s slaves, seemed to fear what the future would bring.

It’s important, I think, to fully embrace the reality that the entire country—the North as well as the South—allowed separation to take root and spread. How and why that happened is the story of Separate. As I write in the Prologue, Plessy is a reminder that history is made, not ordained.

RELATED CONTENT

Readers’ Discussion Guide

1. Did it surprise you to learn in Separate’s opening pages that separation was born in the North, on a Massachusetts railroad, in 1838? Did it set the stage for you to read the book through a different set of eyes than you might have otherwise? If so, what did you conclude?

2. A year before the Civil War, several Louisiana newspapers wrote approvingly of new laws designed to push free people of color into leaving the state for good. If you had been living at that time, in that state, what would you have done? Would your skin color have affected your answer?

3. The Civil War plays a prominent role in Separate’s narrative. Two of the book’s main characters—John Harlan, the lone dissenter to the Plessy ruling, and Albion Tourgée, the lead lawyer for the New Orleans committee that brought the case—fought on the Union side. Henry Billings Brown, who would later write the majority ruling in Plessy, hired a substitute (as many others did). Do you think these men were shaped by their war experiences? If so, how?

4. As a young man fresh out of Yale in 1856, Henry Brown did something unusual for the time—he spent a year traveling in Europe. He called his tour “the most valuable of my life from an educational point of view.” He proclaimed that his trips abroad gave a “wonderful expansion” to his ideas (p. 66). Do you agree? How do you think Brown was shaped by his experiences?

5. The wedding of Malvina Shanklin and John Harlan brought together two families with opposing views of slavery. Mallie said her uncle, “an out-and-out abolitionist,” would “rather have seen me in my grave than have me marry a Southern man” (p.33). When she arrived in Kentucky to start married life, she found an enslaved maid waiting to take care of her needs. Discuss how Mallie reconciled herself to her situation. Do you think her upbringing played an important role in Harlan’s evolution from slaveholder’s son to the lone dissenting judge in Plessy? Can you think of examples in your family of conflict arising from deeply held political or religious views?

6. As John Harlan recruited soldiers for his Union regiment in October 1861, he spoke to large rallies in the Kentucky countryside about his reasons for calling the Confederacy his enemy. As Luxenberg writes (p. 124), “He was taking up arms, he said, to restore the Union. He would not fight a war against slavery, and he prayed that Lincoln did not make it one.” What do you think of his stated position? Was it defensible? Do you think the Union could have been restored if slavery had been allowed to continue?

7. The marriage of Albion and Emma Tourgée was unusual for the period. Emma engages in politics and resists the idea that motherhood is her main calling. Albion tells her that too many men treat their wives only as “instruments for legally indulging” their sexual passions, which he says is “wrong, vile, inhuman (p. 159).” Do you see them as a team in pursuit of racial equality? Would Albion have been able to achieve his considerable ambitions without Emma’s help? Which is a greater factor in Albion’s character, his ego or his evolving anger at the way people of color were treated?

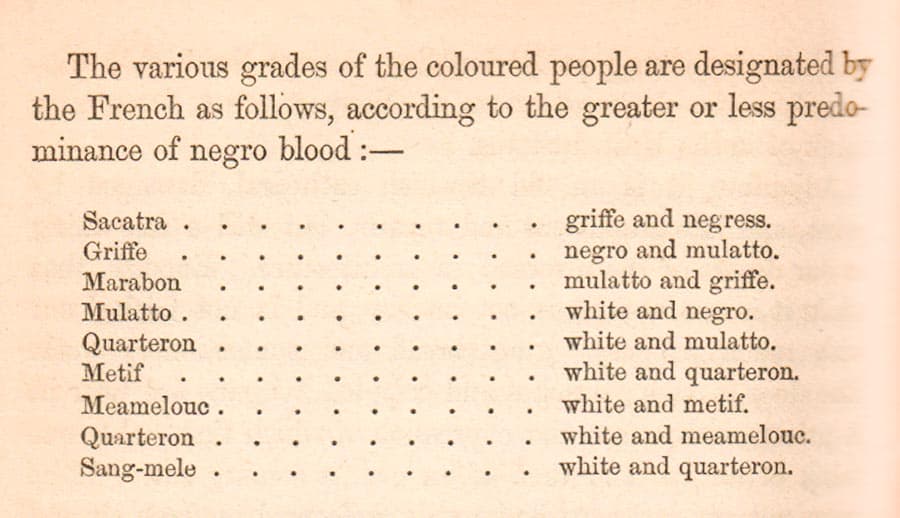

8. A New York journalist, in a visit to New Orleans before the Civil War, was left reeling by the city’s racial spectrum. He developed a racial classification chart (p. 90) with nine categories, “according to the greater or lesser predominance of negro blood.” What impressions did you have of les gens de couleur libres, the French-speaking free people of color? Had most of them not been free for generations, and had not amassed some wealth and education, do you think they would have organized themselves into a committee to test the constitutionality of the 1890 Separate Car Act?

9. Near the end and after the Civil War, the resurgent Republicans in Congress pushed through three constitutional amendments that fundamentally altered the original document and reversed the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott ruling. The amendments abolished slavery, confirmed citizenship for all native-born Americans, established the concept of equal protection regardless of color or race, and extended voting rights to black men. Do you think the Republicans in Congress acted too quickly? Or were the amendments necessary to end the conflict over slavery once and for all? How would you compare the current Congress to the ones of the 1860s and 1870s?

10. Congress also enacted three major civil rights bills, including one in 1875 that guaranteed equal access to public accommodations. Had the Supreme Court not overturned the 1875 act as an unconstitutional intrusion into states’ rights, do you think the country could have avoided decades of segregation, denial of voting rights, and increasing violence against people of color? Or do you think it was inevitable that the end of slavery would result in whites finding new ways to assert their dominance?

11. Had the Supreme Court had not reversed itself on segregation in 1954, what do you think our country would be like today? Do you see a connection between the white supremacists who visited Charlottesville in 2017, and the white supremacists of the 1880s and 1890s?

12. In 1875, while serving as a visiting judge in the Memphis federal court, Henry Brown engineered an invitation to a dinner with a legendary Southerner in residence there. Brown wrote later of his evening with Jefferson Davis, former president of the Confederacy: “I am bound to say I never spent a more delightful evening (p. 309).” Does Brown’s desire to dine with the enemy’s political leader say anything about his personality and temperament? Had Brown fought for the Union during the war, rather than hiring a substitute, do you think he would have been so keen to meet Davis?

13. Separate introduces readers to a long line of resisters from the nineteenth century. Many pursue their fight for equal rights in court, rarely with any success. Were their efforts in vain, even if valiant? Would you have suggested a different strategy? Were lawsuits a better avenue than, say, legislation in Congress or the states? Why or why not? Do you see a connection between their efforts and the civil rights activists of the 1960s?

14. In 1883, Frederick Douglass implored a National Convention of Colored Men to take strong action against the color line, and not settle into a “servile and cowardly submission” to bigotry” (p. 362). Louis A. Martinet of New Orleans was one of the delegates. A decade later, Martinet and his committee asked for Douglass’s support for their challenge to Louisiana’s Separate Car Law. Martinet was furious when Douglass declined. Do you think Martinet was right to expect Douglass’s backing? What might Douglass’s reasons have been? What do these internal divisions suggest to you about the complicated nature of resistance movements?

15. Finding a mixed-race passenger who looked white was a central element in the New Orleans committee’s legal strategy. Tourgée and his main partner on the committee, Louis A. Martinet, planned Homer Plessy’s arrest carefully, trying to create the ideal conditions for their attack on separation. One of Tourgée’s more unusual contentions: Race is a form of personal property, and because being seen as white was economically advantageous, forcing Homer Plessy to sit in the black car amounted to a “forcible confiscation” valuable property (p. 469). Do you think Tourgée made a mistake by being too creative? Were his more conventional points, centering on the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, overshadowed? Or do you think the case was nearly a lost cause from the outset, making Tourgée’s inventive approach understandable and even necessary?

16. Henry Brown’s majority ruling in Plessy was limited, essentially saying that the Louisiana legislature had acted within its “police powers” by enacting a law that separated the races on railroads within the state. Luxenberg’s narrative points out that Brown, usually careful to stick to the legal issues at hand, strayed into personal observations about race relations. Brown said (p. 479) that if people of color felt separation amounted to a “badge of servitude,” that was their fault, because they were choosing “to put that construction on it.” What did you think of such comments by Brown, a Northerner who spent his formative years in the company of antislavery men? Was Brown reflecting the North’s exhaustion with the “Negro question,” as it was frequently called in public debates?

17. As the lone dissenter in Plessy, Harlan cemented his reputation as a clarion voice for fairness and equal protection. What did you think of Harlan’s evolution from proslavery congressional candidate in 1859, to Kentucky attorney general opposing the three constitutional amendments in 1866, to Republican convert in 1868, and finally, to the court’s only consistent advocate for equal rights? Do you know people who have gone through such a dramatic transformation in their political views? What factors influenced them?

18. In his advance praise for the book, bestselling biographer Walter Isaacson said: “Every paragraph resonates with today’s headlines.” Do you agree? Do you see parallels between the nineteenth century confrontations revolving around separation and racial injustice, and today’s battles over questions of race? Did immersing yourself in the world of Separate help you to understand the country’s continuing divisions along racial lines?

Buy the Book

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

IndieBound

Books-A-Million

W.W. Norton

eBOOK

Kindle

Apple Books

Google Play

Nook

Kobo